Jujutsu is the generic name for the grappling arts which samurai trained as a supplement to weapons systems. Not all samurai were skilled in jujutsu and in fact most focused almost exclusively on weapons arts.

Originally jujutsu evolved from the methods used to fight at close quarters when wearing armour. Even though the samurai did not wear heavy metal armour as Europeans did, it still restricted how they could move and what parts of the body were exposed to attack.

Toward the end of the ‘age of the warring states’ (Sengoku Jidai) the martial arts practised by the samurai began to be codified and emerge as distinct methods, known as ‘ryuha‘ today. Among these schools, perhaps the Katori Shinto Ryu is the best known. This is a comprehensive martial art which practise a wide range of weapons as well as some jujutsu technique. Another school which emerged around the same time was the Takenouchiryu school. This too included weapons training but had a greater emphasis on grappling (jujutsu) skills.

The Katori Shintoryu and the Takenouchiryu are just two examples from many hundreds of schools which emerged. Among those focus on grappling, there were estimated to be in the order of 170 different schools. They used different terms for their arts – jujutsu as a descriptor came into use later – so that even today, systems which we might classify as jujutsu, actually use terms such as Yawara, Wajutsu, Kumiuchi etc., to describe their grappling method.

In the Edo period, which extended from the late 17th century, Japan existed in a period of relative peace with no major wars. The country was ruled by the Tokugawa clan Shogun and society had a strict hierarchical structure. Among other aspects, the Shogun required all clan leaders (Daimyo) and their retainers (the samurai) to spend alternate years living in Tokyo (then called Edo). This led to the growth of Edo as an urban centre, and provided a huge cultural melting pot as different clans converged on the city from the far corners of Japan.

Edo soon grew to a population of over a million residents – long before any other city in the world did. As part of this cultural nexus, the fighting arts developed away from the focus on armed battlefield warfare toward dealing with the everyday situations which prevailed in the city.

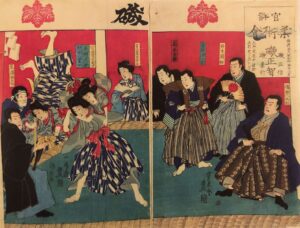

Consequently, the jujutsu schools emerged and developed to focus on fighting methods appropriate to their time. They became more sophisticated, made use everyday clothing so that strangles and chokes could be deployed and they developed more varied methods of restraint using joint locks and throws to subdue and control an opponent. The techniques were divided into standing and seated techniques and the teachers began to write these down as lists of techniques and issue licences to the students who had completed the study of part or all of the curriculum.

Some of the jujutsu schools included striking techniques (atemi) usually aimed at vital points (kyusho) and they obtained quite sophisticated medical knowledge, so much so, that some jujutsu teachers also became doctors or bonesetters (sekkotsuin) – people who could be called on to fix broken bones or treat other injuries or illness.

After the end of the Edo period, Japan began to modernise, creating and adapting its political and legal institutions based on western imperial models. Martial arts were marginalised for a time as the country sought to build an army and navy based on those of Britain, France and Germany. Martial arts teachers struggled to earn a living and many martials arts were simply lost through teachers ceasing to practice.

The saviour of martial arts practice, was Kano Jigoro who founded Kodokan Judo. Kano was a university student who wanted to learn jujutsu. He eventually found a teacher of a jujutsu school called Tenjin Shinyoryu and practised for several years until his teacher died. Kano then continued to train in a school called Kitoryu, until eventually creating Kodokan Judo.

Kano was an educator, he saw an opportunity for jujutsu to evolve into physical education by stripping away some of the more dangerous practises and evolving the training method. He undertook this process within a 10-year period, but he did so with the support of some talented jujutsu practitioners. Kano’s greatest contribution was the creation of randori, by which judoka could freely practice their techniques without harming their opponents. A lot of jujutsu teachers joined the Kodokan and became judo teachers, but continuing to teach jujutsu alongside of judo. So far as freeform grappling (randori) was concerned, the randori of jujutsu disappeared since it could more easily be done in judo training, so jujutsu practice gradually shifted to focus on pair kata training only.

Eventually, judo emerged into a much more popular system which could be taught and practiced by everyone. By the late 19th Century though, the Judo system was often still referred to as jujutsu and it was common for people to practice both. One person who did this actually came from Manchester and took up work in Yokohama in 1897. His name was Ernest Harrison, a journalist who enjoyed Lancashire catch wrestling. Arriving in Japan, he took up jujutsu practising Tenjin Shinyo Ryu before moving to Tokyo where he joined Kano’s Kodokan Judo. Harrison is famous in British Judo history and trained in Japan for about 20 years, leaving the country in 1917.

Harrison was not the only westerner with an interest in jujutsu at that time. By some accounts Edwardian period Europe became quite fascinated by the stories of jujutsu which travellers to Japan wrote about. Some invited Japanese jujutsu wrestlers to come to England and tour the music halls. They gave displays of their skills and took on challengers for cash prizes. Most were doing some sort of hybrid of judo and jujutsu. Among them was Gunji Koizumi, who had practised several jujutsu schools including the same Tenjin Shinyoryu which Harrison had trained in. Eventually, Koizumi became interested in Kano’s Kodokan Judo and this led to him establishing the Budokwai dojo in London, which still exists today.

A lot of other jujutsu and judo wrestlers toured the music halls across Europe and America. One of these was a teacher call Maeda Mitsuo. Maeda is most famous for teaching Gracie, the Brazilian wrestler. Gracie evolved what he learnt and eventually this became the BJJ form which is enjoying immense popularity today.